Resistance to Mining is Increasing Around the World

On September 9, 2015, Canadian mining company Minera IRL announced that it had suspended operations at the Corihuarmi gold mine in Peru, after a group of one hundred protesters took over the site with the goal of stopping production. By midday, Minera shares had dropped by more than 13 percent.

The same week, another Canadian mining company, Nevsun, was defending itself against claims that the company used forced labor at its copper mines in Eritrea. Another headline announced that a lawsuit between mining giants Rio Tinto, BSGR and the government of Guinea had exposed allegations of corruption by the companies during business dealings. A silver mine in Guatemala operated by Canadian company Tahoe Resources was being “fiercely” protested by local communities in the country, resulting in shootings and deaths. And yet another headline told of more than one thousand workers at a South African gold mine who staged a sit-in to protest the deaths of fellow workers at the mine.

Alongside these troubling news stories, a mining-industry website published a handy guide about how mining companies can avoid human trafficking during the labor acquisition process while still “protecting profits” - a surreal addition to the week’s harrowing news cycle.

These stories weren’t presented as a compilation of the worst news of the week; it was simply another week in the resource extraction industry. But with violence becoming increasingly common at mining sites around the world, it’s imperative to ask: what’s going on in the mining industry?

An Industry On The Ropes

Stories like the ones described above typically fall under the radar of mainstream news outlets. Most of the time, only industry-focused publications cover the protests, strikes, and out-and-out conflicts that accompany mining projects worldwide, as these events have a direct impact on investors’ returns and companies’ bottom lines. But while such problems may seem far away from the jeweler’s bench, it’s important that wholesale and retail jewelers have a nuanced understanding of how, exactly, the precious minerals they sell find their way into their shops.

With limited context, it’s easy for audiences to dismiss mining protests as misguided or irrelevant; it is only by examining the on-the-ground realities of mining operations that we can hope to understand why so many people in affected communities are willing to risk their safety, even their lives, in efforts to stop resource extraction projects in their tracks.

The North Mara Gold Mine, Tanzania

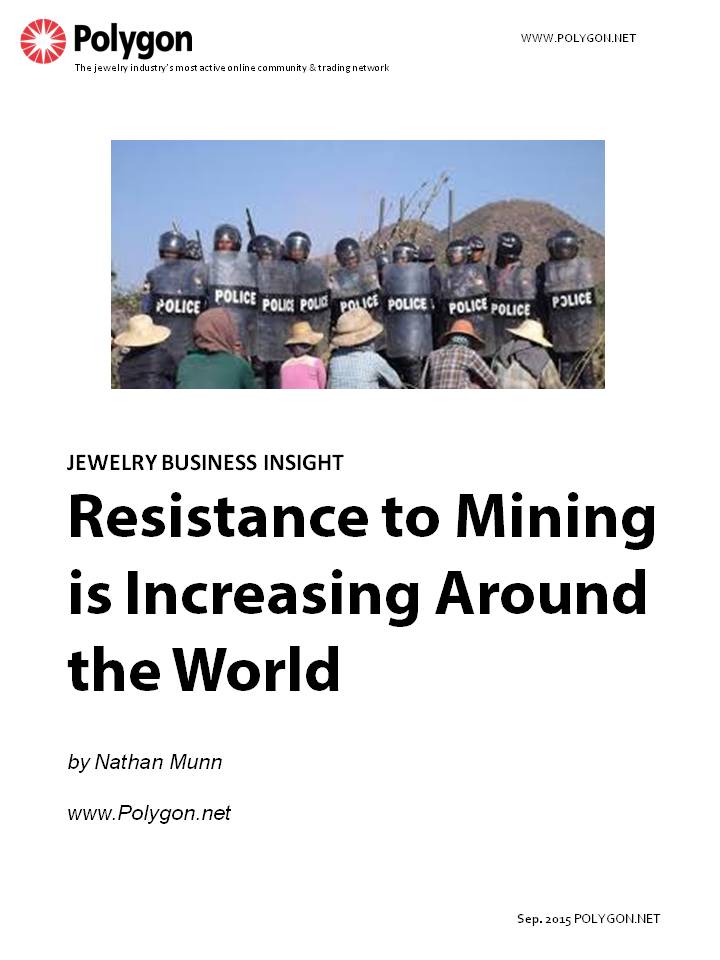

As indigenous peoples in South America, Africa and elsewhere step up their efforts to halt mining in their communities, companies operating in contentious areas have turned to local governments for protection from disaffected populations.

How far are state and corporate interests willing to go to protect their profits from the very communities that they purport to support? In some cases, the answers seem troubling.

In a 2014 article published by Vice News, journalist Chris Oke details how the North Mara gold mine in Tanzania, owned and operated by Canadian miner Barrick Gold, has been a source of anguish for local residents ever since the mine opened in 2002.

According to Oke’s investigation, the region where the mine is located had been being exploited by local, small-scale miners for generations before a concession was granted to Placer Dome (another Canadian mining company that was bought by Barrick in 2006) to mine the area. Once the license was granted, some local miners were compensated for their loss, but many others were denied compensation and refused further access to the area. Many of these artisanal miners, now without livelihoods, continued to enter the mining zone illegally to scrounge for small amounts of gold.

To protect the integrity of the Mara mine, local police forces began to attack the trespassing miners with deadly force.

According to local councilor Wilson Mangure, between 2011 and 2014, 69 people were killed by police forces at the mine; hundreds more were shot, beaten and injured. As a result of the violence, Barrick Gold has been sued in the UK by the families of six individuals who have been killed at the hands of police.

In addition to deaths and injuries suffered by the scavenging miners, it was also revealed that more than a dozen women had been assaulted by police and security personnel at the mine. The women were compensated with settlements from Barrick and offers of employment.

Despite these horrific allegations, it’s important to note that the presence of Barrick Gold hasn’t been entirely negative for the community. Barrick has funded the construction of a high school, contributed to repairs at a local hospital, fixed roads and operates a program to provide clean water to communities near the mine.

But for many residents, these contributions do not make up for the destruction that the Mara mine has brought to their lives.

Resistance to Mining: A Global Reality

Unfortunately, the situation at the Mara mine is not unique. Organized resistance to mining projects is on the rise around the world, driven by legitimate concerns about the negative consequences of resource extraction for affected communities. Tragically, instead of being addressed humanely and comprehensively by those in power, acts of community resistance are often met with state-sanctioned intimidation and violence, as is the case in Colombia.

According to a report published by Peace Brigades International, at least 20 trade unionists in the Colombian mining sector were on the receiving end of physical attacks or assassination attempts in 2010. Additionally, 80% of all human rights violations that occurred in Colombia over the past decade took place in mining and energy-producing municipalities.

While these figures pertain only to one country, they are representative of on-the-ground realities that are present at mining locations in Central and South America, Africa, Central Asia, and other regions where workplace protections are weak or non-existent. For example, a staggering 34 miners were killed by police forces in South Africa on a single day in 2012. Why? The striking miners were demanding better pay from platinum producer Lonmin.

If mining companies and foreign governments aren’t willing to address these issues, what can diamond, gem and precious metals dealers do to help change this situation?

Conflict-Free Gems and Fairmined Precious Metals

Increasingly, average consumers are voicing concerns about the provenance of precious gems and metals they buy. This trend gathered steam with the mainstream recognition of ‘Blood Diamonds’ and conflict minerals, and has now become a major consideration for retail jewelers, especially when catering to younger customers who have a particular interest in buying conflict-free. While certifying diamonds conflict-free does not automatically solve all of the problems associated with mining, it does set a minimum standard by which consumers can determine if a retailer is at least attempting to source stones in as ethical a manner as possible.

Beyond buying lab-grown diamonds – an excellent way to ensure that a diamond’s history is blood-free - buying certified conflict-free diamonds, gemstones and certified Fairmined metals the surest way to ensure that gems and precious metals have been ethically and responsibly sourced.

Hoover and Strong, an iconic American wholesale producer of precious metals, sells certified Fairmined gold, silver and platinum. Among diamond sellers, Zale and Blue Nile both have put policies in place that guarantee all diamonds sold by the companies are conflict free, with harsh penalties outlined for suppliers that violate those terms.

These steps by large companies to support more accountability in the jewelry industry provide an excellent starting point for change. But until industry and governments are willing to work together to design more effective protections for communities affected by mining, extraction sites worldwide will likely continue their transformation into areas of contention, controversy and conflict.

Nathan Munn | Polygon.net